“It’s actually very, very scary.”

That’s how Amnon, a 33-year-old architect born in Tel Aviv and based in Brussels, feels about the current state of his home country.

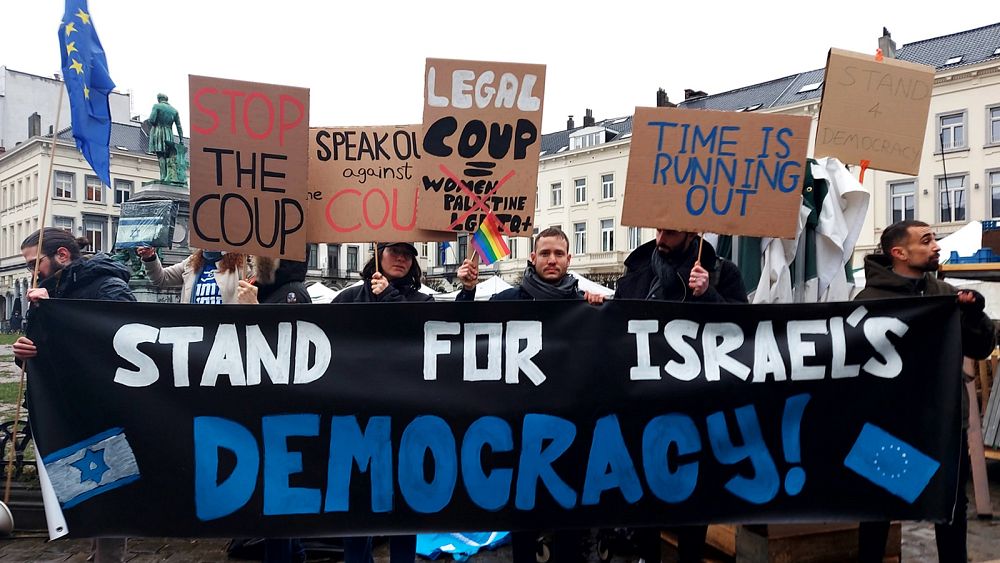

“We are in a crucial moment of saving democracy,” he said, holding a placard that read “legal coup.”

Israel is in a total uproar over a planned judicial reform that aims to remake the fundamental relations between the three branches of government. Protests have taken place on an almost daily basis in a bid to stop – or at least pause – the draft legislation, which critics say will severely undermine the role of the Supreme Court and give free rein to the executive.

Academics, students, business owners, tech investors and even the armed forces have expressed discontent regarding the proposed overhaul, while the country’s president, Isaac Herzog, has warned of “constitutional and social collapse.”

The outcry has now reached Brussels following a demonstration in front of the European Parliament on Wednesday afternoon that culminated in a letter sent to the leaders of the main EU institutions pleading for a more forceful intervention in the debate.

So far, Brussels has kept largely quiet on the evolving reform and prefers to wait for the final version of the law before fleshing out its views on the hot-button topic.

“We won’t speculate on any potential future outcomes of ongoing domestic discussions taking place within the framework of the democratic institutions in Israel,” a European Commission spokesperson told Euronews.

“It is not for us to comment on this matter while the discussions are still taking place.”

‘It’s the end. Game over’

For protesters, though, this response falls flat.

In interviews with Euronews, they described feelings of anxiety and fear over Israel’s democratic status, drawing a parallelism with Hungary and Poland, two EU countries that have been repeatedly accused of encroaching upon judicial independence for political gains.

“By the time the EU speaks, it might just simply be too late. The 75-year experiment of Israeli democracy might come to an end, and only then the European institutions will say what the implications are,” said Dan Sobovitz, the organiser behind Wednesday’s demonstration.

“We’re not asking for sanctions. We’re not asking for the European Union to harm Israel. We are here because we love Israel and we want to save it as a democracy.”

Protesters worry that if Israel ceases to be seen as a fully-fledged democracy in the eyes of the West, its diplomatic and economic relations will seriously deteriorate, with harmful consequences for students, researchers, artists, investors and even energy suppliers.

“I’m afraid for my family and for my friends. And in a way, (Israel) not very much of a democracy now already, but the symbolic democracy will also be ruined,” said Amit, another demonstrator.

In a brief statement to Euronews, Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied the reforms would impair bilateral relations with the bloc in any way.

“Israel has long enjoyed a strong and fruitful relationship with the EU. We look forward to further building and expanding our connection with the European Union well into the future,” the statement said.

“Dialogue between the State of Israel and the EU is carried out through the appropriate channels, and will continue to do so.”

Asked if the judicial overhaul could affect Israel’s participation in Horizon Europe, the EU’s €95.5-billion research programme, a European Commission spokesperson said Israel’s membership was an “opportunity” to deepen cooperation on global challenges, climate change and the digital economy.

For those who are taking to the streets, this kind of reassurances ring void and do little to placate their despair.

“If this reform will pass, the minorities in Israel will feel just out of place,” said Guéva, a 28-year-old artist who joined the rally in Brussels.

“We’re not going to have the Israeli state anymore. It’s going to just disappear and become a dictatorship. And it’s the end. Game over.”

Checks and balances

The judicial reforms have been the source of enormous controversy ever since they were tabled by the ruling coalition of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which has been described as the most right-wing and religiously conservative formation in Israel’s history.

Netanyahu, who is on trial for fraud and bribery charges that he denies, and his allies argue the plans are necessary to curb what they describe as the overreach of the Supreme Court and redirect power to elected representatives in the Israeli parliament, known as the Knesset.

Under the plans, the Knesset will be able to override rulings issued by the Supreme Court with a simple majority of 61 lawmakers. This means that if the Supreme Court strikes down a new law because it is deemed unconstitutional, the Knesset will be empowered to salvage the law and push it through.

Another element of the reform proposes changes to the Judicial Selection Committee (JSC), which promotes and removes judges. Today, the JSC is composed of three Supreme Court justices, two government ministers, two lawmakers and two representatives of the Israel Bar Association.

The current system compels the committee’s political and professional members to find consensus for new appointments but the reform will redistribute seats and give an automatic majority to those stemming from the executive and legislative branches, making it easier for the ruling coalition to decide the makeup of courts all across the country.

The reform will also affect the authority of the Attorney General and legal advisors in ministries, and restrict the Supreme Court’s ability to review administrative orders.

Dr Guy Lurie, a senior fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, a non-partisan research centre, worries the overhaul will remove the Supreme Court as the most effective check-and-balance in a country that has a unicameral parliament, a ceremonial president and an unwritten constitution.

“These reforms, in their complete context, will diminish the protection of human rights in Israel to a large degree and will turn the Supreme Court into a political court that is controlled by the government and will limit its ability to protect the rule of law and civil rights in Israel,” Dr Lurie told Euronews in an interview.

“There will be no effective check on the power of the government and any kind of parliamentary coalition will be able to pass any type of law that it wishes.”

The draft legislation, which is split into chapters, is currently undergoing readings in the Knesset’s committees before being sent to the full plenary. Critics have decried not only the content of the proposed plans but the haste with which are being processed. Meanwhile, opinion polls continue to show a consistent majority opposing the far-reaching reforms.

“I hope it will be stopped, or at least very, very seriously amended,” Dr Lurie said.

“Right now, it’s being pushed forward with just one very narrow side of the Knesset supporting it without any attempt to reach a wide consensus.”

This piece has been updated to include new reactions.

Leave a Reply